The UK’s Space Agency has failed to get a National Space Strategy off the ground more than three years after the Tory government first drew up the plans, a National Audit Office (NAO) report has revealed.

The agency is still in the "early stages" of implementation and is struggling with a 20% staffing shortfall and a similar number of temporary staff, the spending watchdog said in its report on “The National Space Strategy and the role of the UK Space Agency”.

The agency, created under the aegis of the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology (DSIT) on April 1 2010, has suffered from a lack of "clarity" on exactly how much money the government was spending on space-based initiatives overall.

It has more work underway than it can afford to continue "without a budget uplift” beyond next March and was warned that there may be “difficult decisions” ahead.

"The government did well to draw its many different interests and activities in this very diverse sector into a single vision in its 2021 national Strategy, which set high ambitions and helped galvanise the sector’s interest," the report stated.

"DSIT recognised that the original Strategy was broad and that it did not know how much it would cost to deliver. However, it did not produce the implementation plan that it had originally planned to, and three years later DSIT and UKSA are still in the early stages of identifying and developing the plans and capabilities needed to deliver the Strategy’s ambitions."

The NAO’s report landed 24 hours after the new secretary of state for DSIT, Peter Kyle, used his first ministerial speech to laud the importance of space at the Farnborough International Airshow, and announce millions of pounds in investment for new projects.

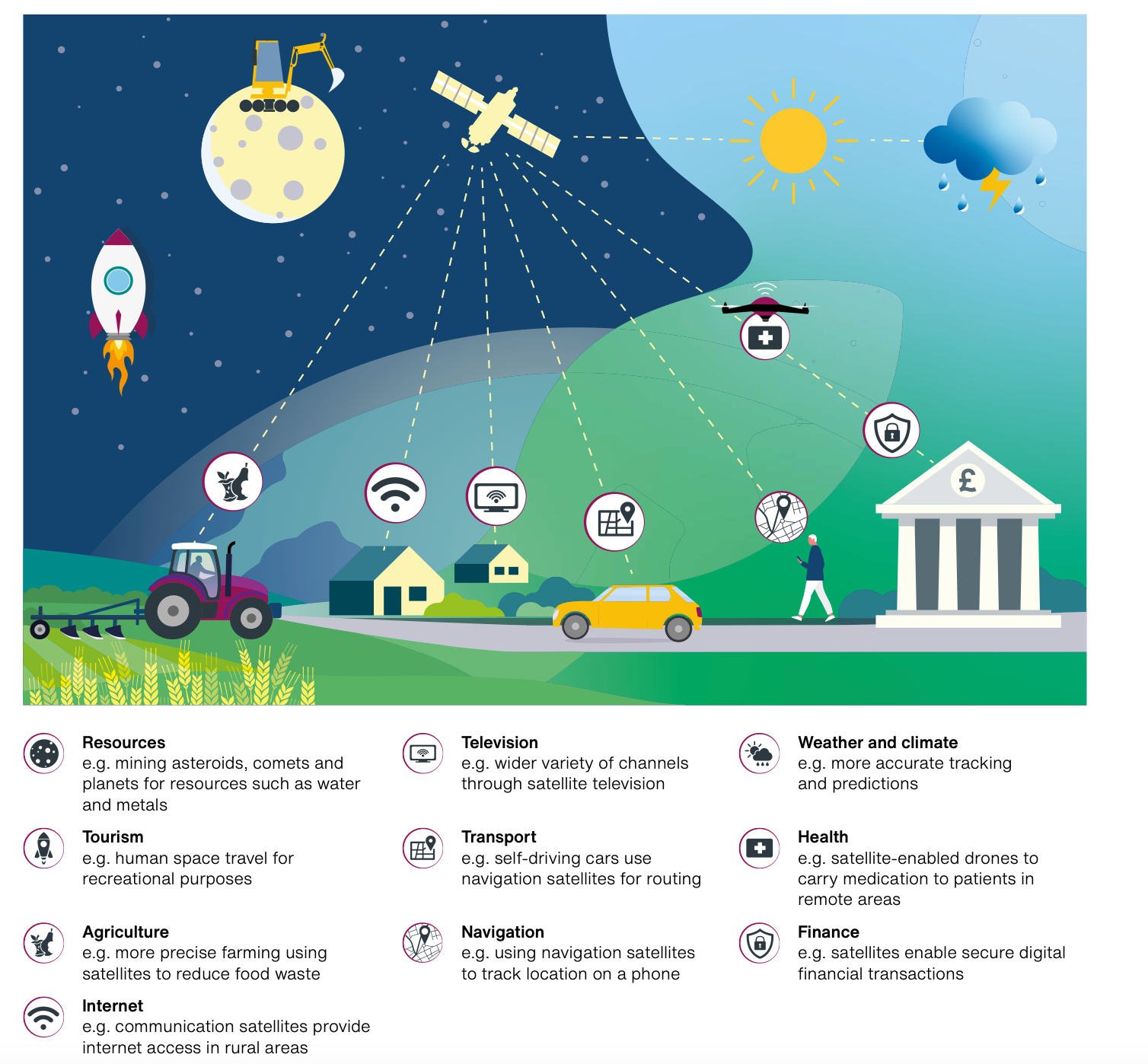

Kyle told the audience that “there is no better example than the space sector that explains what we are trying to do as a government.” He said the industry was growing four times faster than the UK economy overall, and its workforce was twice as productive as the UK average. He flagged up its role in national security, as well as communications, and in fundamental science research, including drug development.

However, the NAO’s report detailed how the previous administration set a cross-government National Space Strategy in 2021 but failed to set out budgets, while a cross-governmental ministerial council on space put off meeting for two years, only reconvening in July 2023.

The NAO found that DSIT itself “has not provided enough clarity or detail on its strategic ambitions to allow delivery bodies and stakeholders to plan to achieve them” and had failed to set out specific plans, priorities, or a time frame. A previous minister had rowed back on delivering a detailed “implementation plan," raising the possibility of both “gaps or duplication.”

READ MORE: How Japan's space agency used dashboards in its race to the moon

This could be one reason why a 2023 guide to the UK Spaceports listed no less than seven facilities across the UK, of which three were in Scotland. So far, there do not appear to have been any successful launches from the UK.

And, it continued, DSIT itself “does not yet fully understand the government’s overall funding to and requirements for the space sector.” While the UKSA’s spending grew from £373m in 2018-19 to £647m in 2022-2023, other agencies are also throwing cash into space.

The UK Space Agency itself was “proactive” in aligning its activities with the national strategy, but a transformation strategy due for March 2024 will not now be complete until 2025. Processes for allocating the agency’s £1.75bn budget for 2022 to 2025 had “some weakness”, the NAO found, “but they are improving the approach for the next spending review period.”

Although the UK has been a big contributor to the European Space Agency, the UK "does not yet receive contracts from ESA proportionate to the value of the funding UKSA provides.” This is despite 85% of the UKSA’s spending heading to ESA, and the European agencies’ aim to allocate contracts proportionately. The UKSA is working with its bigger European partner to rebalance this by the end of this year.

Meanwhile, the agency is experiencing delays in building business cases for funding approvals, partly down to “a lack of capability and capacity to produce them.”

This may be because the agency itself is struggling to fill its desks, with a fifth of positions unfilled as of March this year, while 21% of current staff were temps, “which risks corporate memory being lost, can be more expensive and can limit how effectively an organisation or certain teams are run.”

In the meantime, the NAO called on DSIT and other government bodies to better map the “roles and responsibilities of public bodies with a role in the space sector” and better coordinate government spend on space activities by December this year.

And by June 2025, it should “assess whether there will be sufficient funding to achieve its ambitions and identified capabilities. Should there not be sufficient funding, DSIT should update its plans, setting out what would be deprioritised together with its longer-term funding ambitions.”

All of which casts a shadow over the agency’s plans for the future. However, with the new chancellor expected to cut billions of pounds of projects due to the hole in the public finances being even bigger than expected, that shadow could get even bigger.