High-quality data, ratings and research is crucial for anyone wanting to take sustainable investment strategy seriously. But the sustainabililty data marketplace remains confusing and inconsistent.

As regulators and institutional investors around the world ratchet up pressure on enterprises to deliver more comprehensive reports on their emissions and beyond – e.g. via the EU's landmark NFRD* -- digital strategy leaders can expect to be more involved in company reporting and ESG programmes.

Indeed, there is scope for senior IT figures to take real leadership roles, as demand for unstructured data grows, and as new API and cloud-based tools emerge to help automate such non-financial reporting.

A new report by the European Commission aims to help asssess the state of play and may prove a vital cheat sheet for those looking to familiarise themselves with the sector. It's a chunky 214-pages however.

The Stack's team digested it for time-poor readers seeking quick insight.

*Non-Financial Reporting Directive. Effective 2018 and applicable to over 6,000 large organisations

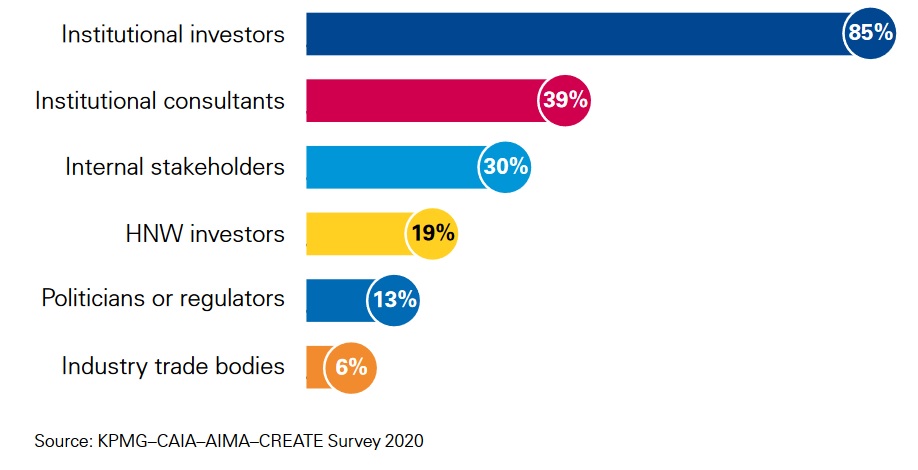

1: Who's driving demand for ESG data?

It’s institutional investors who really piling pressure on companies to disclose ESG data. Larry Fink, the CEO of BlackRock – an asset manager with over $7 trillion under management – famously told chief executives in an annual letter at the start of 2020 that, going forwards, the firm would avoid investments in companies that “present a high sustainability-related risk.” BlackRock has since doubled down. Others have followed suit.

Climate change is almost invariably the top issue that clients around the world raise with BlackRock, Fink recently reiterated. A mid-2020 survey by the firm of 425 investors in 27 countries representing $25 trillion under management found that respondents plan to double their sustainable assets under management in the next five years – rising from 18% of assets under management on average today to 37% on average by 2025.

Most are chafing at the absence of high quality ESG data, however: more than half (53%) of BlackRock’s respondents cited the poor quality or availability of ESG data and analytics as the biggest barrier to broader and deeper implementation of sustainable investing.

2: Who's buying ESG data?

The biggest buyers of "ESG data" are asset managers at 59%, followed by sell-side institutions at 19%, asset owners at 12%, other, including consulting firms and investment advisors, at 6% and corporations at 4%.

(Source: ESG Data Market: No Stopping Its Rise Now, Opimas, March 2020, as cited in the EC's "Study on Sustainability-Related Ratings, Data and Research", January 6, 2020).

3: What is that data?

The data used by investors/research providers can be broken down into three main categories.

a) Company disclosures: Data direct from companies (mandated or voluntary); and span a mix of quantitative and qualitative data. Few stick to the same format or guidelines and few make it machine readable, however. b) Alternative company data: Unstructured company data (or alternative data) includes information about the business not released through formal company channels. This can span media reports, NGO reports, geospatial data and more. c) Third-party data: Third-party data could include data from either of the above two categories that has been collected, packaged and/or analysed and sold to the data and research provider.

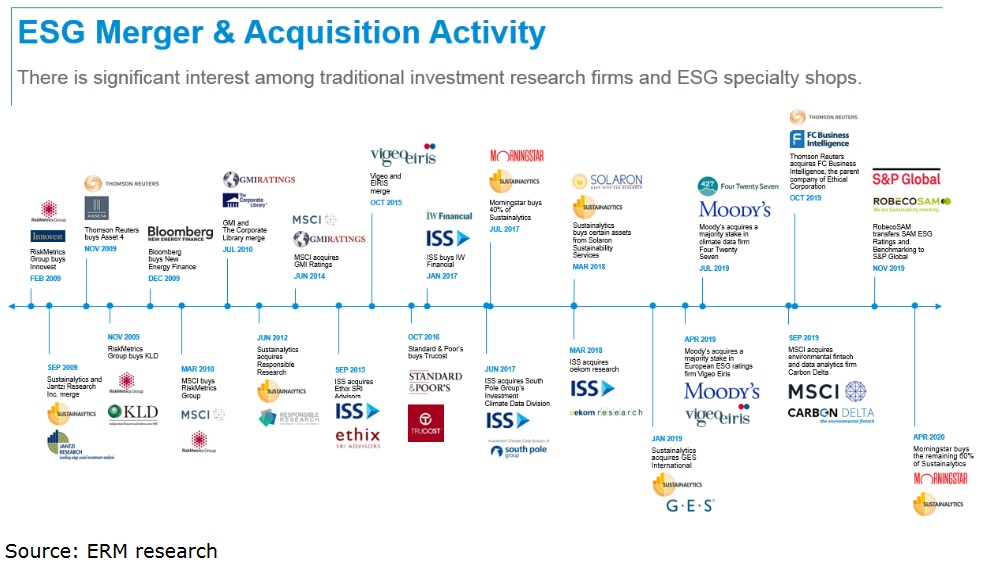

4: Who are the big players in the sustainability data marketplace?

KPMG puts the number of substantive sustainability-related rating and data providers at ~150 worldwide. There's little harmony or standardisation between them, though numerous efforts are afoot to change that.

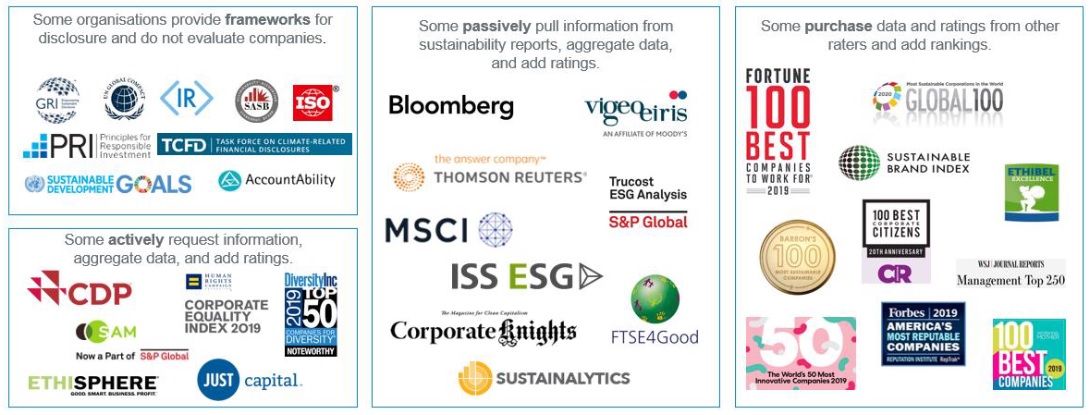

As the EC notes: "Sustainability-related product and service providerscan present sustainability-related information to users in different forms, including data aggregation, ratings, rankings, screening/weighting services, research, benchmarks, voting advisory, controversy reports and financial product assessments."

Companies indicate providers not only have an issue with timeliness, but also with accuracy and reliability.

Ratings, in particular, may focus on specific sustainability performance or on financial products, such as evaluating a specific fund’s ESG performance. Providers of these products and services include: Bloomberg, MSCI, Sustainalytics, ISS, FSTE Russell, S&P, Vigeo Eiris, Refinitiv (formerly Thomson Reuters) and others.

(In a reminder of just how immature this market is, even industry giant Bloomberg only launched proprietary ESG scores in August 2020. This initial offering includes Environmental and Social (ES) scores for 252 companies in the Oil & Gas sector and separate "G" scores tracking board composition (a narrow metric) across 4,300 companies.)

5: Standard setters and framework developers...

There's no shortage of other movers-and-shakers in the ESG data market.

Standard setters, for example, publish detailed guidelines that support companies in understanding what ESG-related information they should disclose, by topic. These include the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), CDP (formerly the Carbon Disclosure Project), Climate Disclosure Standards Board (CDSB), International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) and Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB).

"Help, I'm confused..."

As law firm David Polk and Wardwell LLP tidily notes:

"GRI standards generally enable companies to report sustainability information that significantly impacts the economy, environment or people and, in turn, the companies’ contributions toward sustainable development. SASB standards and the CDSB framework generally focus on sustainability information that they view as material to corporate value creation. CDSB’s framework focuses primarily on “a company’s natural capital, environmental and climate-related risks and opportunities.” In contrast, SASB standards are industry-specific and span across five subcategories of sustainability information, “including the environment, social capital, human capital, business model and innovation, and leadership and governance.” The IIRC, meanwhile, provides the integrated reporting framework that connects sustainability information to financial reporting.

Then there's the framework developers like the UN Global Compact, the GRI 10 Reporting Principles and the TCFD, which are more focussed on "principle-based concepts for how a report is structured."

To round up...

In 2020, 90% of all S&P 500 companies published a sustainability/responsibility report.

ESG data tends to be "an assortment of complex datasets requiring different specialisations" as the EC report notes, however. As with any "Big Data" challenge, such data tends to be fragmented, not standardised, not machine readable and often hard to come by.

See also: Climate risk data is a hot mess. These open source pioneers want to set things straight.

Data providers remain frustrated at the poor quality and format of reporting by many companies. (A host of startups are emerging to help make that process less painful). But the frustration goes both ways...

As the EC notes: "Companies continue to express concerns about the timeliness of updates to their profiles within the various sustainability-related rating, data and research provider outputs and systems... Companies indicate providers not only have an issue with timeliness, but also with accuracy and reliability. Providers that state that AI and other automated search tools are keeping information up to date, also have errors."

Stepping back a little, there are other macro-level issues. As Eurosif, a responsible investment organisation, noted in early 2021 however, for all the virtue of using such ESG data to drive investment to cleaner companies and encourage others to change their ways, metrics that look to combine carbon intensity or carbon footprint with economic values such as the value of investments or revenues run the risk of driving investments to "traditionally low carbon business models (e.g. pharmaceuticals vs transport) [when it is...] exactly the transition of these high-emitting sectors that will determine whether or not we will achieve the race to net-zero.

Eurosif adds: "To avoid this, we recommend that company-specific forward-looking climate metric should compare between companies within the same industry and versus the industry-specific transition pathway to achieve net-zero."