Material from a horrific data breach earlier this year at a UK company holding the details of thousands of IT contractors revealed that staff were routinely storing credentials in clearly flagged Word or Excel documents -- titled, among other examples, “useful links and passwords”, “passwords”, and “useful passwords”.

The Stack's readers, hopefully, do not need reminding that storing credentials in plaintext on easily accessible documents is a diabolical idea, but we will spell it out: It makes it exceptionally easy for an initial intrusion or cybersecurity incident to escalate without the need for any technical nous whatsoever.

Now it appears that the Lapsus$ hackers may have accessed a spreadsheet of 'domain admin' passwords on the network of third-party IT provider Sitel -- the company used to compromise Okta -- in an incident that puts fresh attention on the importance of a) basic security hygiene and b) supply chain/sub-contractor security risk.

The news comes as today’s annual Cyber Security Breaches Survey raised real red flags.

As James Griffiths, co-founder of Cyber Security Associates (CSA) noted "[the report identifies] concerning findings around the supply chain. Only 13% of businesses have assessed the risks posed by their immediate suppliers, with organisations saying that cyber security was not an important factor in the procurement process. Yet between 55% and 60% of businesses are outsourcing their IT and cyber security to an external supplier."

In which we are unkind about WEF’s Global Cybersecurity Outlook

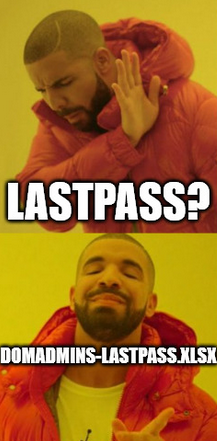

Documents seen by security researcher Bill Demirkapi (who had his employment at Zoom terminated for sharing them) include a timeline of the Sitel intrusion by incident response specialist Mandiant that suggests the hackers found and accessed a spreadsheet on Sitel's network called “DomAdmins-LastPass.xlsx” -- i.e. pointing to passwords for domain admin accounts exported from the LastPass password manager. (It also revealed that the attackers made the initial breach via a VPN gateway on a legacy network belonging to Sykes, a customer service company working for Okta bought by Sitel in 2021: M&A risk is, as CISOs know, a perennial issue.)

The incident serious head-shaking across the security community, although Sitel denied it had been quite that careless, saying on March 29: "Several media articles have falsely alleged that a spreadsheet was disclosed that contained compromised passwords and contributed to the security incident.

"This 'spreadsheet' identified in recent news articles simply listed account names from legacy Sykes but did not contain any passwords. The only reference to passwords in the spreadsheet," Sitel continued, without furnishing evidence of this "was the date in which passwords were changed per listed account; no passwords were included in this spreadsheet. Such information is inaccurate and misleading and did not contribute to the incident."

See also: Linux Foundation wants “more cooperation” from US Government on 0days

Regardless, the company continues to have questions to answer.

As Demirkapi notes: "Why did your customers have to wait two months to even hear that you were breached? Sitel Group serves many more customers than Okta. Often times, for support staff to perform their jobs, they need Administrative privileges into their customer's environment. The attack highlights the increased risk of outsourcing access to your org.'s internal environment", adding "good questions to ask include: Who knows how your sub-processors handle their own security? As we saw in this case, Sitel didn't take the security of their environment very seriously. What can an attacker do if one of your sub-processors becomes compromised?"

As former GCHQ Director Robert Hannigan has noted, knowing where to start when it comes to supply chain risk can be a challenge: "The scale of the supply chain ecosystem for most companies is so large that they have no choice but to prioritise, trying to identify those suppliers that are ‘critical’. But traditional priority categories don’t necessarily work for cyber because they may not be where the risk comes from.

"The top tier of business critical suppliers will probably include household names, major cloud service or software providers who spend a lot on their security and are very good at it; but it may ignore the long tail of the supply chain where the threat may actually come from" he has added: "These are likely to be smaller companies with very limited security capabilities and awareness..."