Flying home to the US from Japan, security researcher Sam Curry got the fright of his life. Pulled aside for what he thought was a standard secondary security check, he was met by officers from the IRS Criminal Investigation (IRS-CI) service and Department of Homeland Security (DHS) who presented him with a Grand Jury subpoena – which demanded he appear in New York to provide testimony for wire fraud.

Curry, a staff security engineer at blockchain technology company Yuga Labs, told The Stack: “They did it in a way where I felt like I was – I found out later that I was! – the actual subject of the investigation. I was kind of panicked; freaking out because I realised that they had flown two agents out to basically wait until I got off my flight…”

As he put it on X: “I'd given my unlocked device to the inspecting officer, but then watched as it was passed to the DHS and IRS-CI agents who were investigating the money laundering, conspiracy, and wire fraud charges. After they'd questioned me, I was asked to leave the room while they sat and searched through my unlocked device for another hour. At this point I'd been given almost no information on whether or not I was a subject, witness, or anything related to the case at all.”

After being let out, Curry sought legal help quickly: “I left immigration around nine or ten at night, got in touch with a lawyer and they told me to fill out a memorandum about the interview to make sure that I remember it correctly and then they basically begin the process of reaching out [to the DHS et al] to get as much information as they could [about the looming case] and let them know that I was happy to answer questions or talk about it with them, because I didn't feel like I've done anything wrong.”

So what had happened?

It transpired that “I was the target of the grand jury subpoena and for a really silly reason” Curry explained: “Back in December, 2022, I helped investigate a crypto phishing website that had stolen millions of dollars.

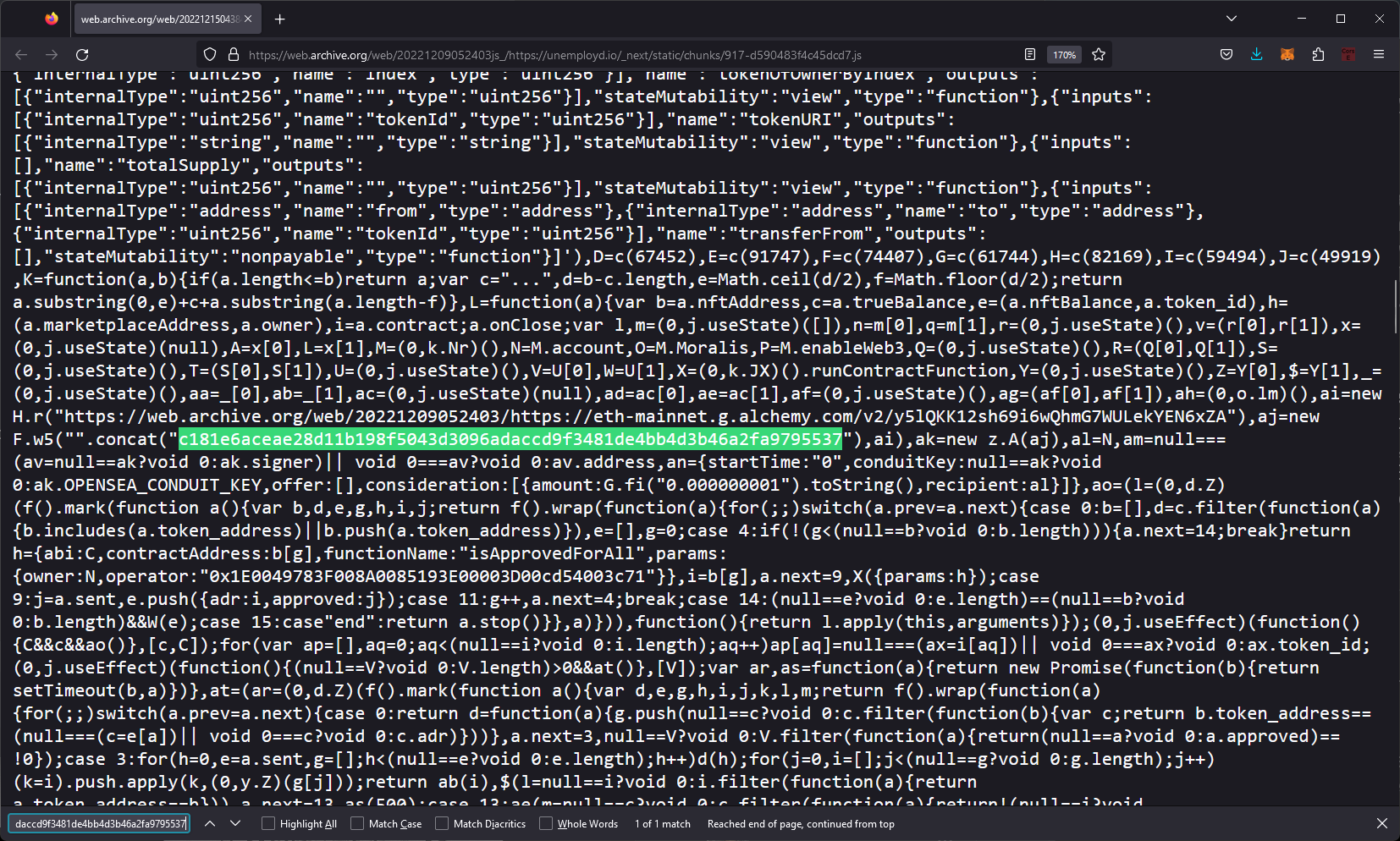

“In the JavaScript of the website, the scammer had accidentally published their Ethereum private key. Sadly, I'd found it five minutes too late and the stolen assets were gone” he explained in an X thread – adding to The Stack that "investigating phishing websites is a really interesting area of research. Sometimes you can find their private key and save people money."

“During this process, I'd imported the private key into my MetaMask [crypto wallet] and navigated to OpenSea [a web3 marketplace] to check if there was anything left in the wallet. When I did this, I was on my home IP address and obviously not attempting to conceal my identity as I was simply investigating this. The agents had requested the authorization logs of the account from OpenSea and saw my IP.

“They subpoenaed the IP, found out who I was, then decided to use immigration as an excuse to ask for my device and summon me to a grand jury, rather than just email me or something. After emailing back and forth for a few hours, the lawyer was able to get the subpoena completely dismissed and confirmation that all data from my device had been deleted. It's odd to me that they didn't see I work as a security engineer who responds to these things regularly” he added.

Curry told The Stack: “The goal with me sharing [this incident] is that there's a lot of people who do similar [security] research. If [government investigators] are not willing to give me the benefit of doubt – they obviously had all the information about me and understood who I was, but they were willing to assemble what felt like an ambush where I'm getting off a flight and I have these two agents [waiting] -- it makes me worried for the other people who investigate these sort of issues. It's a situation where if you don't have a good lawyer, you have to fly down to New York, testify under a grand jury about something you didn't personally do; it's a haywire experience, you can't sleep and you could get pulled into years of legal battle."

The indictment has now been dropped, he said, thanks to his company's swift legal support and clear understanding somewhere further up the food chain with prosecutors that they had not snared a master villian who had stupidly forgotten to jump on Tor. That quick outcome (within days) was a huge relief, he said; whether prosecutors should have realised earlier that they were wasting time and resources is an open question. The Stack has contacted the DHS for comment.

The incident comes a year after the Department of Justice said it will no longer pursue hackers who breach networks or computers in "good faith" – adding: "Good faith security research means accessing a computer solely for purposes of good-faith testing, investigation, and/or correction of a security flaw or vulnerability, where such activity is carried out in a manner designed to avoid any harm to individuals or the public, and where the information derived from the activity is used primarily to promote the security or safety of the class of devices, machines, or online services to which the accessed computer belongs, or those who use such... online services."

The announcement came amid revision of DOJ policy around how it will charge apparent breaches of the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA); 1986 legislation that multiple courts of appeals have used to hold hackers civilly or criminally liable for accessing or probing a system for vulnerabilities without permission.