James Gfrerer, a former United States Marine Officer who spent three years as commanding officer of the Marine Corps' Information Operations Center, was well placed -- as a veteran with 20 years military experience -- to head up the sprawling US Department of Veterans Affairs as CIO from 2019-2021. (The role is a political appointment and Gferer, previously an executive director at EY, now runs his own tech consultancy).

Gfrerer was brought in to provide stability and experience to the VA after a series of major IT and other leadership issues at a department that had earlier been described by lawmakers as "rudderless." (As Pacific Standard notes: "In 2018 alone, an IT mistake left tens of thousands of veterans without housing allowances, and the start of a $16 billion electronic medical record overhaul was overshadowed by political infighting.")

Among his challenges of leading the strategic digital role at the organisation was ensuring strong spending transparency as the department swelled in size: VA is close to 420,000 employees now, up from just 140,000 employees ten years ago. It has a ~$4 billion+ IT budget and runs some 800+ applications.

As the experienced CIO notes: "The one thing I always challenged folks with during my tenure, was at what point do we declare that we are a technology organisation that delivers health benefits and memorial service outcomes? Because the technology is such a critical component of how our business delivery model works.'

The Stack joined Gfrerer to talk cost control, innovation, and Technology Business Management (TBM) -- a set of standards and best practices to communicate the cost, quality, and value of IT investments.

IT spend opacity had been a big issue at VA. How did you tackle it and how did TBM translate at the coalface into a useful toolkit to do so?

It's arguably ironic, although a good thing, that IT spend has met with this focus amid a proliferation of IT spending around Covid. I often think of the apocryphal Sir William Slim quote: 'Gentlemen, we are out of money -- it's time to think.' And I think the opposite can be the challenge when you're awash in cash: how are you applying those finances? How are you getting the right levelised and prioritised investment and being a good steward of the taxpayer's dollars? Because government agencies do not always have a P&L mindset.

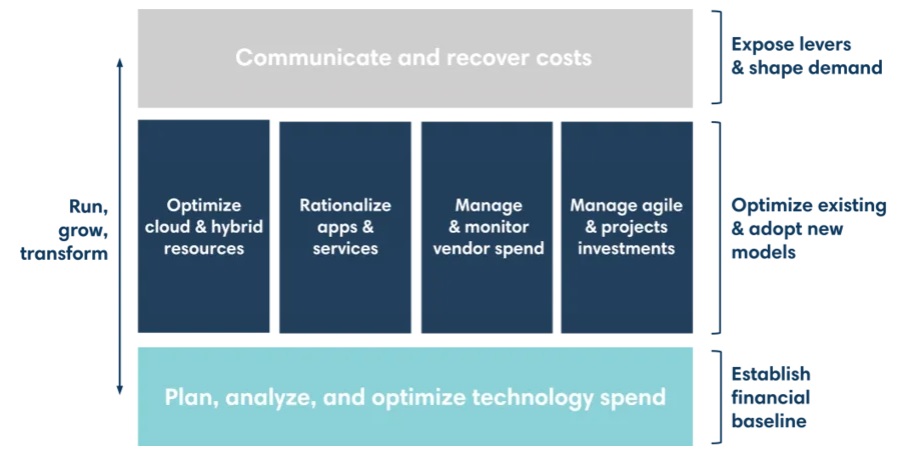

Any CIO really has three responsibilities: you have to run the enterprise, you have to grow the enterprise, and you have to transform or modernise it. Each of those three buckets requires a certain amount of investing. I think the biggest challenge is, over time, most spending gravitates towards the operations and maintenance, the 'run' bucket. And in growing organisation like VA with the demand on technology -- more mouths to feed; more applications to maintain and develop; an exponential increase in the technology -- that's a real risk.

Follow The Stack on LinkedIn

I think the challenge for any IT leader is that journey from being seen as a cost centre to a value driver.

I think we really changed this mindset at the VA -- where IT started having the conversations and asking the tough questions about what is the time to value? What is the cost avoidance for the business? What are the the tangible outcomes that technology is helping deliver? And part of it was a very selfish conversation, because we always wanted to baseline and tie that to increased investment; having having done it since the 90s.

Because the challenge for CIOs often is that you take processes in the line of business, you automate them or apply technology to them and you're lifting and shifting that cost into the back office. There's rarely, if ever, a corresponding investment that transfers with that additional cost, that's really the challenge.

A criticism - particularly of federal organisations/the public sector - has been that IT cost becomes a bit of a Black Box...

Thatt was one of the early challenges we had -- and we were able to finally remedy that by using TBM. We started by breaking it [IT spend] down by the portfolios in the case of the electronic medical records: to get better, more refined cost accounting. Because, as you might imagine, those costs are distributed across multiple pillars within the Office of Information and Technology: you have a security component, you have a development component, you have an acquisition component; there's a personnel and a staffing component.

The ability to aggregate all that cost data and to give a really bottom line number is sometimes elusive. But we were able to do that, thanks to the TBM Framework -- we used the Apptio suite for this.

We also had some unfunded requirements that were adjudicating through the C-Suite. One of them that did not hit the must-pay threshold was our four trusted internet connection gateways: I can tell you that after March 13 2020 presidential emergency declaration [on the pandemic], that went from a no-pay to a must-pay!

One of the things we really highlighted was that you can have the best applications in the world, the best internet-connected devices and lines of business; but if you don't have the infrastructure, and the support and the shared services to support those and you go dark or you lose availability, what does it matter? There was also a little bit of tyranny of the commons going on, with the whole notion of enterprise or shared services: people think they're free…

How much was cloud OpEx management an issue for you at VA?

A significant one.

The great thing about cloud though is because of the billing across storage, compute and the other aspects, we were able to do two things at the very least -- again, all with the aid of Technology Business Management.

The VA has a enterprise cloud, which has two principal vendors: Azure, and AWS. Both of them, like any cloud service provider, are able to provide that real-time feed of cost and performance data. So the TBM model could ingest that, and it really allowed us to have near real-time (or certainly monthly) conversations around our obligation rates. Then correspondingly, it allowed us to take talk about shared services again; for example to take care of core platform costs around the enterprise cloud and decompose or burden those costs down to the product line manager. We were able to give our 32 product lines very real-time data around costs and how they're executing. Then we were also able to take the platform costs, and say: 'Hey, here's your corresponding share of the shared services!' That really provided that FinOps transparency and accountability,

The black box is a wonderful thing to lines of business, because they can literally say, 'I didn't know'.

Well, you do now, right?!

So again, the TBM construct really allows us to capture that cost to decompose it by product line.

I think the other brilliant thing was it allowed us to take the cloud budget, which from a FinOps perspective become a big target. The lines of business for the CFO or somebody could look at a large cloud number and say, 'Wow, it costs you, say $500 million to operate the VA enterprise cloud?' That's a big target from an accounting and cost avoidance perspective. But if you show that it decomposes into 32 product lines, it's providing X value, and here's the overall cost by X product line, it becomes a much better business conversation.

To get that clarity you need to pull good data from across your product lines too. How easy was that?

The VA grew up as independent entities. It was a healthcare administration; separately, a benefits and memorial services and some other entities in the late '80s. And over the past 30 years, the department has struggled to integrate those data feeds.

A good example from a veteran's perspective is there's a core document that every veteran gets, when they leave service: a form called called the DD214. That really is your statement of service; the baseline eligibility document. As a veteran who uses VA [myself]s it's stunning how many times we make the end user, the veteran, submit that document. Seriously, how many times do you have to submit this document?!

Shouldn't there be one version of it that comes over seamlessly as you transition from your active duty military status into a veteran status? How many times should a veteran have to submit that data? The answer is zero: that data should come over seamlessly. When DOD pushes a button, this individual has retired, whatever the status was, and the data [should] transmit over seamlessly to a single repository. And the entire Department of Veterans Affairs should reference that one base document; the veteran never even submits it.

Our va.gov team have done a great deal to collapse this functionality and these data feeds onto one platform. And that's one of the things you'll see change in the next I'd say next 18 plus months.

What guidance would you offer for any other public sector CIO, whether that's in the US or the UK on what you learned at VA?

There was an article recently written by Mark Schwartz, who's with AWS, and he talks about the whole notion of the financial ops aspect of being an IT leader; how not only do you have your current level of spending, which is always going to be probably some deficient number to the business, but you also have a level of technical debt. And technical debt in the purest sense is software debt. We can also characterise that as human capital and hardware debt in terms of infrastructure.

As an IT leader you have to make the case to the C-Suite that -- just like any line of business is responsible for time to value and addressing debt in the year it's incurred -- that IT can be equally responsible. We should be able to show the CFO 'here's our balance sheet, here's our plan to to burn down and address both the technical debt, and the spending within the portfolio. The whole notion of product line is key: if can't really adopt a product line mentality and show them that value that you're delivering and the cadence and pace on what you're delivering it. I think you're relegated to an eternal cost centre status.

Post-VA, what's next for you, Jim?

I've started my own LLC, and I'm working with large IT companies to help serve better in the federal space and public sector. One of the things that comes up as I have various conversations in DC and elsewhere, is how can we get agencies, CIOs and leaders to partner better our IT vendor community to deliver the products and services they need. The vendor community really wants to support the federal government -- and there's plenty of business out there -- but sometimes the government needs challenging on helping them to serve us: from having clear strategies, levelised investment and so on. There's nothing more frustrating than to a line of business, a federal agency, or a vendor to kick off a programme, get into some sort of multi-year engagement effort, only to find that there are funding issues two or three years in.