Intel

"The US and the Western world became far behind our Asian peers..."

Intel’s nascent foundry business lost $7 billion in 2023 and its revenues plunged $8.6 billion on lower internal chip production volumes – nearly a third of Intel’s chips are now made by external partners like TSMC.

High CapEx businesses tend to get caught up in feast and famine cycles and Intel is deep in the “where did all the food go?” bit right now – on a call with analysts this week CEO Pat Gelsinger admitted as much.

The year ahead will be the “trough” as Intel tackles a “process technology deficit” after being “slow to adopt EUV” and builds out the process technologies that will allow it to attract more foundry customers used to co-designing and working with the likes of TSMC, he emphasised.

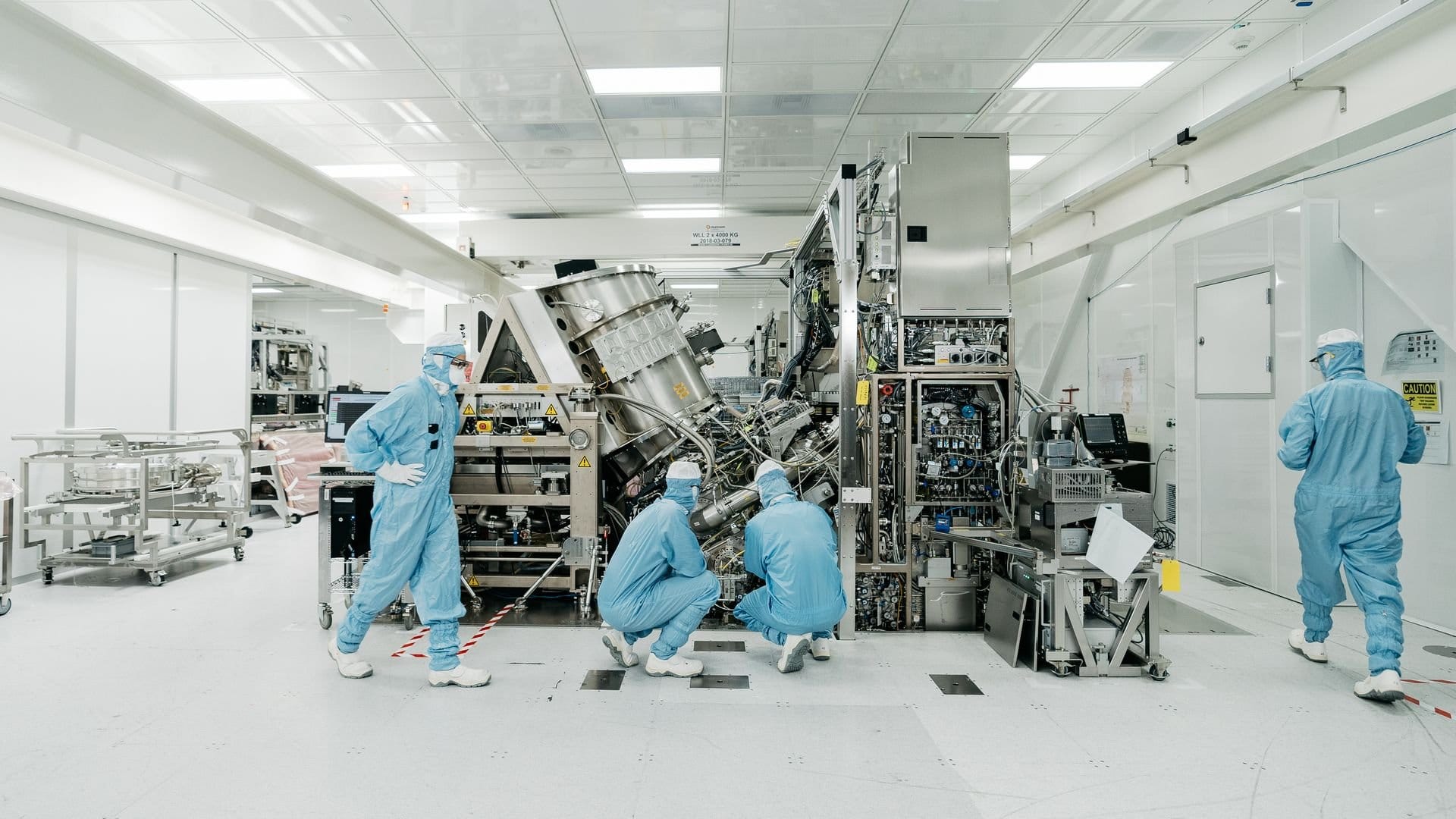

(EUV is extreme ultraviolet lithography; a cutting-edge technique for making chips that relies on light that doesn’t occur naturally on earth: It involves heating a droplet of tin to 400,000 degrees Celsius with a laser, collecting the unusual light that orbiting electrons produce using ultra-flat mirrors, then using it to stamp structures on the surface of specially coated silicon wafers; dear reader, you cannot do this in your bedroom…)

With capital and technological demands shutting more and more companies out of meaningfully competing in the semiconductor-making space (even as AI drives “an explosion in compute needs”, as Gelsinger put it), investors may be biting their short-termist fingernails, but Intel is readying itself for the “feast” end of this cycle, he suggested; be patient.

Join peers managing over $100 billion in annual IT spend and subscribe to unlock full access to The Stack’s analysis and events.

Already a member? Sign in