Hashicorp CTO and co-founder Armon Dadgar spent the summers of 2009 and 2010 as a software production intern for Amazon. Now, a little more than a decade later, he helps steer a successful open source company with a net retention rate of 134% and nearly 4,000 customers; several of which are spending over $10 million annually.

Today, Hashicorp and AWS are both considered major players in the managed infrastructure space. And, while Dadgar and his team don't quite have the trillionaire problems that Bezos and company do, Hashicorp's growth trajectory (and a current $5.5 billion market cap) give them plenty of reason for optimism in 2023.

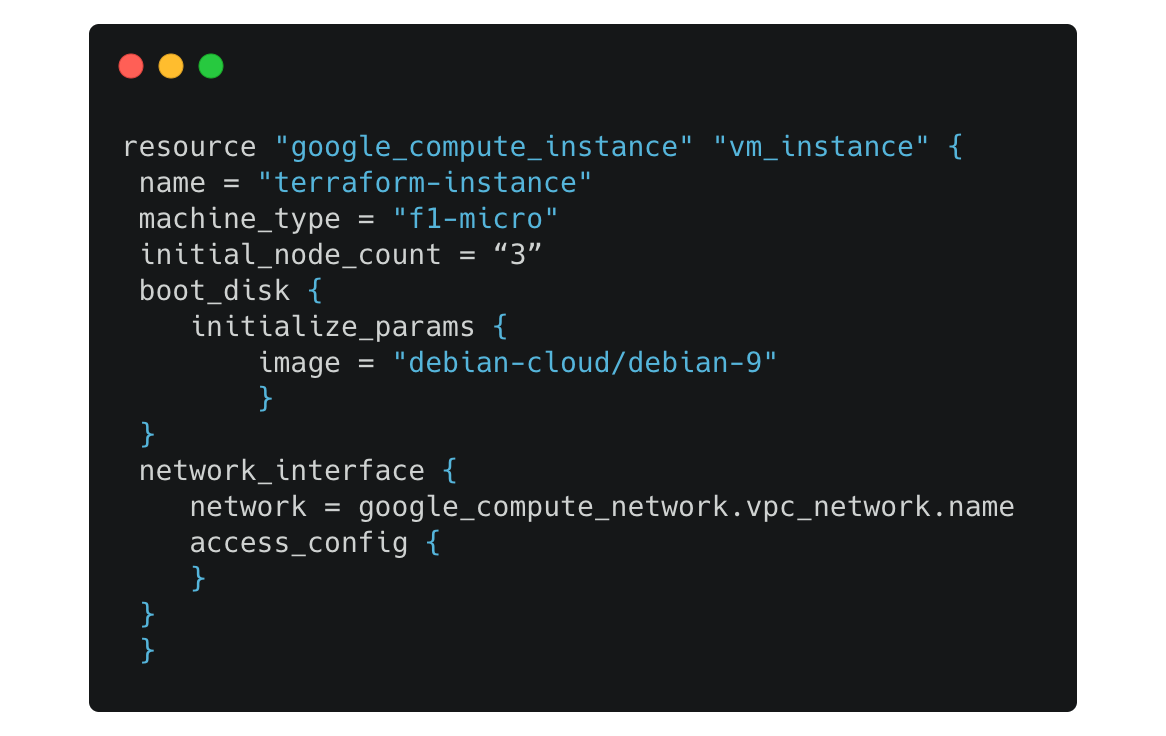

The company’s product suite is growing rapidly – including into Zero Trust with its release of “Boundary” – but is anchored in the popularity of Terraform, an open source Infrastructure-as-Code (IaC) tool used to automate the provisioning of cloud or on-premises infrastructure and re-provision it in response to configuration changes.

The Stack caught up with Dadgar to chat about the road to cloud adoption, fear of automation, why Hashicorp hasn't felt the need to restrict its open source licensing in the same ways that many others have, and more.

HashiCorp CTO Armon Dadgar: Devs are being held back...

Everyone likes to picture seamlessly managed IT infrastructure but the reality is that most IT estates sprawling "frankenstacks" and too many processes across them are still managed manually, increasing friction and slowing the pace at which business can get innovations out to market. As the CTO of HashiCorp puts it: "We look at most of these organisations, [they might have] 1,000 or 10,000, developers, they're sitting there waiting on average, three weeks, four weeks, eight weeks -- we have some companies we've worked with for like six months -- to get these changes done because of the manual process of the organisation. What Terraform does is automate those steps so if a developer wants to make a change, instead of talking to central IT and waiting for six months, they can go and push a button and Terraform will make all those changes for them in a matter of minutes.

(One user, German stock exchange operator Deutsche Börse Group for example, explains in a technical case study how it uses Terraform to manage over 40,000 foundational infrastructure resources and "standardize this foundational infrastructure and, additionally, many of the applications and services running on top.")

Dadgar adds: “That developer wants to plug into some user interface and point and click some buttons to basically provision servers and databases and networks and whatever they need for the application [and] iIt's taking you six months to do it, you have a lot of human error… you have a whole lot of unhappy developers, they're sitting around waiting for this stuff” – and the flip side of the coin, he adds, is “if you're going to automate it, great, you freed up a bunch of time for your IT departments, you're doing it in a much more secure way, you made your developers happy, and you unlocked business value, because you're able to deliver much faster.”

It's through this seemingly simple value – and an army of open source developers working to ensure that Terraform supports literally thousands of integrations – that Hashicorp has managed to coexist with the 500-pound gorillas of the tech world. The secret sauce, according to Dadgar, lies in Terraform's versatility.

Simply put, big tech can't buy the kind of support for integrations that decades of global open source development affords HashiCorp: “From an integration surface area,” says Dadgar, “it's almost infinite.

“The power of that open source community is that it's going and solving that integration problem in a way that no proprietary vendor would really realistically be able to do, the surface area is just too large.”

He adds: “Cisco creates their own integrations. Microsoft creates their own integrations, Google creates their own integrations, Palo Alto creates their own integration, and so on so forth. In the Terraform universe, we have something like 500 corporate partners that work with us, as well as 2,000 individual contributors. Terraform integrates with over 2,500 different types of systems today. HashiCorp maintains maybe 50 of those directly.”

The path to Terraform adoption

With so much infrastructure provisioning still happening manually, Dagdar points to a generational issue. “It's not a technology problem, the technology exists, any one of these organisations can go pick up Terraform tomorrow and start using it. It's really two things. One is a skill set issue. And we see this broadly in the market. You have a generation of people that were trained over the last 30 or 40 years to do it in a very manual, human oriented way. And now we're saying 'don't do it that way at all.' Instead, do it in this automated, programming driven approach.”

It's not that adoption rates are necessarily slow. There's just a lot of potential customers out there and not all of them are ready to make the leap. “We literally do 1000s of Terraform certifications on a monthly basis,” he told us, “but that's a drop in the bucket when you think about how many people are still doing this stuff manually.”

Part of the reticence, Dagdar suggests, has to do with a general fear of automation.

Some senior IT administrators may be under the impression that such tools could threaten their jobs. Most of HashiCorp’s clients aren't using these tools to replace humans, but to free up overtasked developmental teams to spend more time working on problems and less time waiting on processes, however, he suggests.

Making open source work...

HashiCorp has seen open source work for it strikingly successfully. As executives mentioned on its most recent earnings call, one of its largest customers – spending over $10 million annually – “started working with us around a single product and expanded and extended over time. They became a Terraform customer in calendar 2018, then Consul in 2019, and then Vault in 2020 and 2021, starting with our Open Source products in each case.”

It’s an impressive example of land-and-expand in action. To what extent does the company feel the need to make a more aggressive effort to monetise an open source user base, particularly in a world in which companies like Elastic, MongoDB, and Redis have restricted their licenses? None, is the short answer.

Dadgar tells The Stack: “The mistake a lot of open source companies make is they believe that the open source user is also the buyer. And I think that's where you get into a lot of trouble because you end up trying to monetize your user. And then that can get into a situation where the users feel like, you know, they're getting short-changed. The recognition we have is that our open source user is not our buyer. They're the champion. They're the one who's going to bring us into an organisation and be our sponsor, our technical sponsor. Our buyer tends to be these platform engineering teams. And the problem that they want to solve is very different…”

And critically at a certain point, it becomes harder for big tech to ape products like Terraform than it does for them to simply work with Hashicorp like everyone else using the company's open source solutions. This goes back to having a veritable army of open source developers working to forge integrations.

As Dadgar put it: “With Terraform, you need to integrate with 1,000 or 2,000 things. It's very hard to replicate that, there's sort of that natural network effect of, 'hey, we're working with all these vendors in a way that doesn't exist for something like a Mongo.' If you think about a database, you don't need to integrate with 1,000 other things. Your application talks directly to the database, it puts the data in, it reads data out. It's not an integration problem.”

What this means is that Hashicorp can afford to keep its licensing permissive, even while comparative entities who exist in the same commercial, open source operations space have been forced to clamp down on similar use.

He says: “Because we sit in the integration space, it's a slightly different problem. And I think people want that relationship with us. They know we maintain the ecosystem. The second piece of it is that the license is almost less important than the governance structure. And I think what you see with a lot of these open source projects, is that they end up in the governance of these big foundations... and I think that really limits your ability to then commercialise the software. You lose control of your destiny a little bit. We've always been really firm with HashiCorp, software doesn't live in a foundation. It's built by, managed, and curated by HashiCorp.”

Amid a world slowly but arguably inevitably moving away form a moat-and-castle approach to security and the subsequent shift away from VPNs, HashiCorp’s new product “Boundary” is a big focus for the company.

The product lets remote users ssecurely connect to hosts and critical systems “across Kubernetes clusters, cloud service catalogs, and on-premises infrastructure” to help with just-in-time access to privileged sessions (e.g. TCP, SSH, RDP) for users and applications and control permissions with extensible role-based access controls.

It’s not a straightforward march into the SASE space, HashiCorp CTO Armon Dadgar says: “The goal of Boundary is that in the same way you can deploy your app in five minutes on Terraform, can I give you access to that application in real time without having to deal with all these traditional controls… I think a lot of the SASE stuff is almost a call more like cloud VPN; replacing the notion of a corporate VPN. I think for us, we’re more focused on production, access to infrastructure, and how do you make that both an elegant experience, but also fit within the modern development context of cloud applications and, and a [cloud-native] security paradigm.”

BREAK

Stepping back to the infrastructure provisioning space and indeed broader cloud infrastructure market, he sees a huge runway: “The average enterprise that we work with is between 2% and 30% [in the cloud]. I think there's an enormous amount of cloud adoption yet to come over the next five to 10 years. There's a long long tail”.

HashiCorp's mid-term ambition meanwhile is that "everyone in the global 4000 will one day be a customer for us" and with that net retention rate of 134% the possibility of expanding within these companies is significant.

There’s real opportunity for infrastructure modernisation in Europe in particular he adds meanwhile, which arguably is at the forefront of numerous technology sectors — especially those at the intersection of chemistry, physics, and engineering — but mid-pack in the realm of cloud-computing infrastructure and sometimes slow to adapt automation technologies.

As Dagdar told The Stack: “There's a natural conservatism in Europe. 'We don't want to be first.' 'Let's see how it works in America, and then we'll be decisive.'” He sees the Asian market as "actually pretty aggressive. That's a much hungrier market. They really want to compete on a global stage.”

It's time to wrap up: What’s exciting you right now outside of your own product suite, The Stack asks?

“I think the way data tooling is getting democratised. We’re Snowflake customers, DataDog customers, Looker customers… that whole ecosystem’s making it a lot easier to build sophisticated products.

"To me personally, a renaissance of databases [is also exciting]. There's this next generation of startups working on serverless databases, databases running at the edge [bringing a] much better user experience, much better workflow, and kind of modernising the database experience.”

His focus is on helping developers move the needle however and that's a long game, he says: "We have a big developer evangelism function; because that's the front end of this stuff. As they build skills, as they build companies, that might become a commercial opportunity for us a year, two years, three years from now."