GCHQ Director Sir Jeremy Fleming controversially took to the airwaves as guest editor of the BBC’s Today programme on December 29. The career intelligence official hosted conversations with Microsoft President Brad Smith, and US Director of National Intelligence (DNI) Avril Haines, discussed the benefits of diversity and hiring dyslexics, lessons from the war in Ukraine – “a battle where information and intelligence are to the fore” – and politely fended off a light grilling about oversight and indeed whether he should be appearing on the show.

Engaging though his programme was, his guest editorship was a grave error of judgement, writes The Stack's Ed Targett. It came just weeks after the Intelligence and Security Committee -- responsible for overseeing GCHQ's compliance with the rules under which it operates -- warned that its "oversight is being eroded" and that the heads of the agencies it oversees, including Sir Fleming, need to "account for these failures." GCHQ's role is critical. Given its reach, so is its oversight. Sir Fleming's appearance was a clumsy tactical misstep in what his own guest Haines called a "battle over the information space" and reflected badly on the BBC too. Here's why.

GCHQ Director Sir Jeremy Fleming on "Today"

GCHQ’s role is “very intrusive, it’s very unusual” Sir Fleming acknowledged on the programme.

GCHQ’s data mining capabilities are significant. In 2012, for example, it was running over 1,000 machines to process more than 40 billion pieces of internet content a day, former NSA contractor Edward Snowden’s leaks revealed. (These were condemned anew by Sir Fleming on Today as having resulted in “a lot of blood and money and wasted effort”.) It also has the legislatively-sanctioned right to access, with a warrant, the internet browsing history of anyone in the UK. GCHQ has become a lot better in recent years at communicating why this is necessary. It has also improved private sector engagement. (The decision in 2018 to explain when it discloses "zero day" software vulnerabilities to vendors and when it preserves their use for intelligence purposes is a case in point; a move intended to improve communication with a sometimes frustrated cybersecurity community.)

GCHQ, NCSC Technical Director Dr Ian Levy calls quits after 22 years

It does good work with these powers: GCHQ uses its heft not just to take on terrorists and unfriendly nation states, but to help protect UK Plc from malicious cybersecurity attacks. (The NCSC, which sits under GCHQ, now publicly scans every internet-connected device hosted in the UK for vulnerabilities in a bid to help reduce attack surface, using what it describes as “standard and freely available network tools”; The Stack understands that this refers to Nuclei.) It also tackles child sexual abuse, organised crime, and works on counter-proliferation.

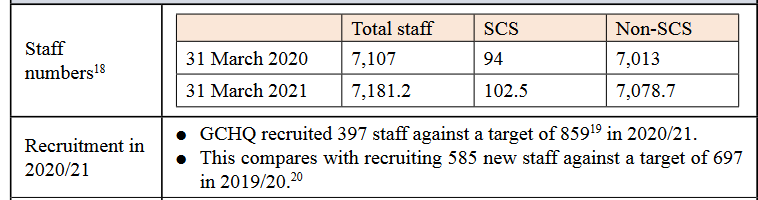

It does this whilst confronting significant staff recruitment and retention challenges. (A sense of mission is important but the ability to triple your salary in the private sector can be hard to resist for many, as can the lure of more flexible working and less bureacracy. GCHQ missed its recruitment target by over 50% for the last year recorded.)

In a dangerous world, few would challenge the critical role of signals intelligence and online data mining in keeping British citizens safe, even if nuances around the balance of those efforts with the right to privacy remain deeply contested. Yet the BBC’s decision to offer editorship of a flagship programme to an intelligence services director soon triggered pointed criticism; even though the BBC has brought an array of guest editors in to “Today” between Christmas and the New Year for the past 19 years. Most of this focussed on reputational risk.

The propaganda expert: “Absolutely horrifying”

One critic of his guest editorship, Dr Emma Briant of Bard College in New York said it was “horrifying to give an intelligence agency editorial control over a BBC flagship news programme. I just find it absolutely appalling,”. Dr Briant, an expert in propaganda told Scotland’s The National: “If they wanted to undermine the BBC’s perception of independence and cause more people to flood to conspiracy theory media then this is the way to do it.”

Dr Rory Cormac – a Professor of International Relations at the University of Nottingham who specialises in Secret Intelligence and Covert Action – also dubbed the decision a “mistake”, saying: “Interview him, yes. Have a bunch of features themed around internet/security etc, yes. But having a serving intelligence chief editing a flagship BBC programme sends the wrong message”, clarifying on Twitter that “giving a serving intell [sic] chief perceived editorial control and ability to set [the] news agenda of [a] flagship show will do nothing to dispel false myths about BBC ‘propaganda’ and [it being a] mouthpiece of intell [sic]. Well-intentioned but misjudged.”

An "assymetric advantage"

There is clearly a larger debate to be had here about the extent to which the intelligence community should be intervening in public debate, particularly in a role as guest editor on a flagship BBC news show; a role egregiously unlikely to result in robust questioning (the BBC's Nick Robinson was certainly more chummy than genuinely probing in his interview of Sir Fleming). This is complicated by the increased weaponisation of misinformation in grey warfare and the rise of troll farms and social media bots working at the bidding of bad actors.

Avril Haines reflected on this on the show, saying: “[We need to] recognise how important the battle is over the information space in so many different areas for our society… authoritarian states have this kind of asymmetric advantage where they're effectively controlling the information to their populations. And we, in fact, not only do we see it, as you know, sort of a benefit of our society, that we're able to have an open information, space and so on, but it's actually crucial to our form of government… Authoritarian states take advantage of [an] open information space and, you know, promote their own narratives and exacerbate divisions in our society.

Join peers following The Stack on LinkedIn

“I think this is something that is sort of a growing area for intelligence communities,” she added.

It is also a growing area that is an infinitely delicate challenge for the intelligence communities. Not least because in those authoritarian states, that same claim that malign forces are working to “promote their own narratives and exacerbate divisions in our society” is a distorted reflection of Haines' words that is regularly used to shut down protest. This makes it all the more critical that, as Sir Fleming put it to the BBC’s Nick Robinson on the Today Programme: “We need to help people understand that not only are we doing things in the right way, when no one is looking, we’re also doing it in accordance with a set of values that I hope people would buy into.”

Walking the walk...

That "set of values" is represented not just in fine words, but expressed through parliamentary oversight.

Sir Fleming said on the show: “We have world leading legislation, which is transparent about the sorts of things that we do, that puts in place, authorization and compliance measures that I don’t see anywhere else in the world, then ultimately, is accountable to a committee in Parliament. So I’m very confident about that regime.”

The GCHQ director might be very confident. That regime is less confident about him and his peers.

Asked by Robinson why he accepted the guest editorship, he said that “I think we have a responsibility to talk a lot about trust, to try and encourage the public to understand what we're doing, to trust in the things we do."

Yet Sir Fleming’s guest editorship came just weeks after the Intelligence and Security Committee (ISC), criticised the “failure of the UK Intelligence Community to meet standard deadlines as part of the ISC Inquiry process” and warned emphatically that this was preventing it from “effectively performing its statutory oversight role.”

That GCHQ’s Director should have taken to the airwaves just weeks after this criticism, and tout its compliance with the UK’s oversight regime – to little pushback from his interviewer – seems tactless at best.

Members of the ISC would be forgiven for feeling it smacks of arrogance.

“Oversight is being eroded”

There is, of course, a bigger political and governance backdrop here that is not in Sir Fleming’s bailiwick.

“Oversight is being eroded” said the Intelligence and Security Committee in December 2022. It was not just pointing the finger at tardy responses to requests for information from the agencies it in theory oversees, but also warning that the government was “actively avoiding the effective scrutiny by Parliament of national security issues” by failing to update the memorandum of understanding that sets its mandate, and allocating oversight of key elements to other select committees that do not have regular access to classified information.

The fact that the Intelligence and Security Committee has not met with the Prime Minister since December 2014 is deeply shocking but not Sir Fleming or his peers' fault. (The ISC met with the Prime Minister to “discuss its work, report on key issues and raise any concerns” annually from 1994 for 20 years).

The fact that the committee feels the need to warn that it runs the risk of being unable to "provide any assurance to the public or Parliament that the intelligence Agencies are acting appropriately, and therefore that they merit the licence to operate that Parliament has given them through their statutory powers" as a result of their failure to respond promptly to questions is a challenge right at his doorstep and one that suggests this is not a time to be on the radio chatting with pals. As the ISC warned just weeks ago: "Despite numerous complaints, the situation has not improved and, if anything, has got worse. The Committee has called on the Heads of the seven organisations it oversees to account for these failures, and to provide assurances on a suitable way forward."

(To be fair, we have little visibility into precisely which agencies of the seven in question this criticism is most aimed at. It may be that GCHQ is the best of the lot at responding to the ISC and the ire is mostly aimed at MI5, in which case we apologise to Sir Fleming, but still feel the timing was wrong and the format inappropriate.)

Senior civil servants may not like MPs. They may be faced with a rotten calibre of elected officials. They may face challenges getting appropriate budgets to keep the country safe, poor salaries and little thanks when they do.

And when it comes to public engagement they are often damned if they do and damned if they don't. Several public sector CIOs have spoken passionately to The Stack about being hampered from talking about the fantastic innovation their teams are delivering because some spotty special advisor for some cognitively challenged junior minister thinks it is not the place of unelected officials to talk to the press. We are loath to perpetuate this tension and generally keen to champion innovation that no doubt it happening in a life-saving way at GCHQ.

But if people of the calibre of GCHQ's director are going to take to the airwaves, touting the wonders of the UK’s oversight regime, they better make blooming sure they’re in ticking all the many boxes it requires of them. GCHQ has big challenges – compliance, talent retention, diversity being among them – that demand attention internally and tough questioning externally. Sir Fleming talked passionately about trust. He will build more of it being seen responding appropriately to fire from the ISC, rather than getting gently flambéd by friends on Today.