A new biological security strategy (NBSS) from the British Government warns that the convergence of bioscience and AI has “paved the way for automated approaches to biology, creating new cyberbiosecurity risk.”

It proposes the ambitious development of a new "National Biosurveillance Network" that would join up "syndromic, epidemiological and promising environmental surveillance capabilities" including sensors capturing data from wastewater and the air that would "flow from the network into the National Situation Centre’s proposed Biothreats Radar, providing... a comprehensive picture of known and nascent biological threats."

Critics will be mindful of techUK's recent criticism that the UK has often put out "strategies and policy papers with high ambitions, however when it comes to delivery, there has been a failure of follow through..."

And although HMG has promised £1.5 billion in funding for this "Biothreats Radar", as Paul Blakeley, life science policy lead at the Tony Blair Institute notes: "Whilst this might sound impressive, it is a fraction of the c. £410bn of public funding spent responding to Covid-19 alone..."

"Potentially extreme risks"

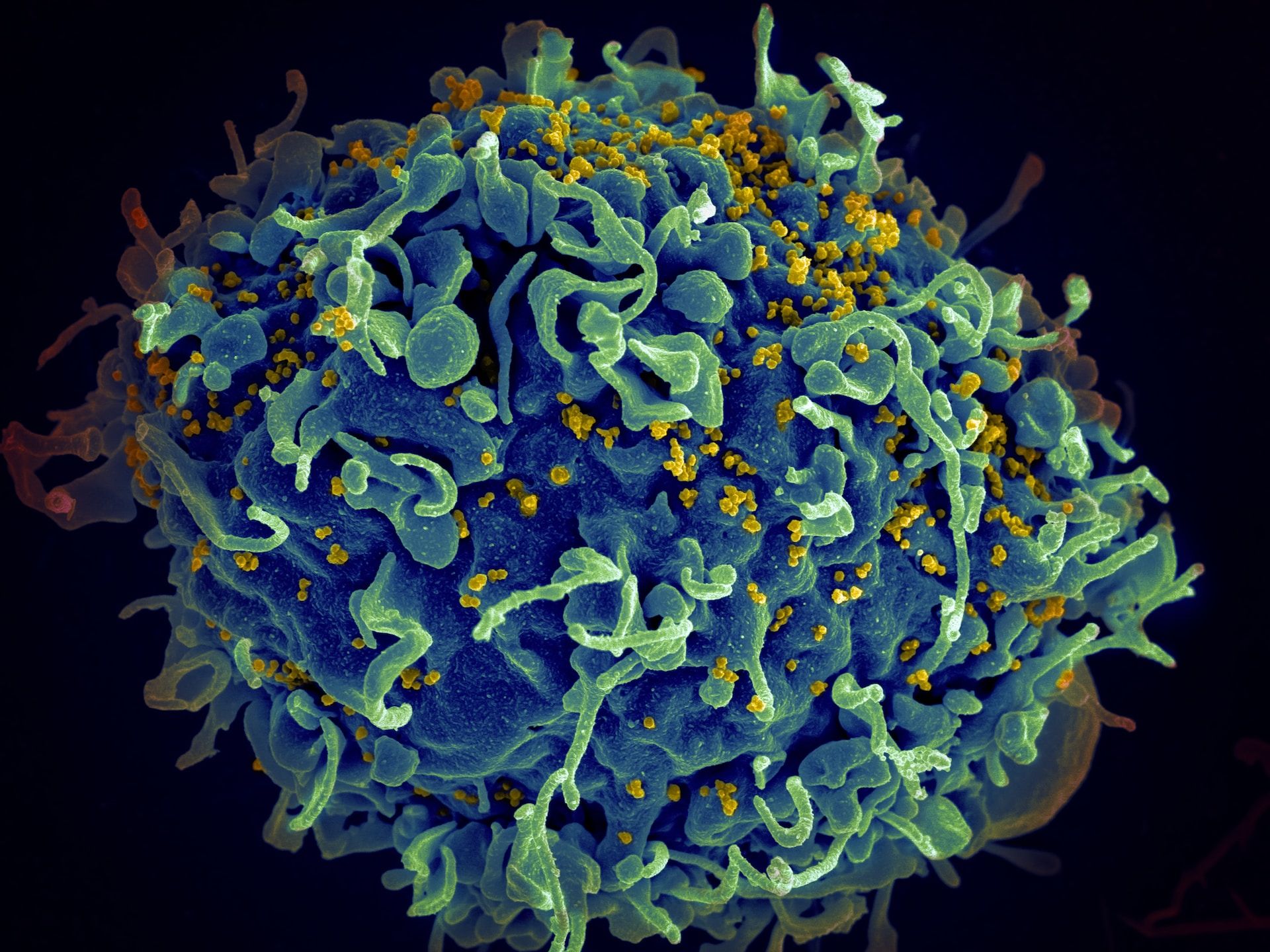

The June 12, 2023 report adds: "As science and technology advances, it also presents new, potentially extreme risks. More people now have the necessary skills to perform high risk research at low cost. Rapidly developing DNA synthesis capabilities used for advancing biomedical research, could also be deliberately misused to build new pathogens..."

Cyberbiosecurity has been defined by leading US academics as a rapidly growing “complex ecosystem of security vulnerabilities at the interface of the life sciences, information systems, biosecurity, and cybersecurity.”

What kind of “cyberbiosecurity” risks?

A 2022 paper by researchers from John Hopkins University, The Wilson Center, Virginia Tech, and Merrick & Co., cited by HMG in its June 12 biological security report points to a range of “cyberbiosecurity” risks including the irresponsible application of AI techniques to biology.

Others include “unauthorized remote access to an automated biological manufacturing system”; a falling cost of entry to synthetic biology including the “convergence of robotics, microfluidics, cell-free systems design and synthetic metabolic engineering” creating “unique threat domains” and “vulnerable critical links and nodes” in agriculture.

UK’s biological security strategy

HMG’s new biological security strategy sees the government try to tackle this risk whilst showcasing “best practice for responsible innovation.”

The strategy is a roadmap that lists out potential moves forward when it comes to solutions such as detection systems, data sharing, regulatory partnerships, novel diagnostics, vaccines, therapeutics, and more.

The NBSS sets out ambitious plans across four pillars: Understand; Prevent; Detect; Respond. Far from all are defensive and HMG said it wants to incentivise technology development against a set of priority biosecurity missions.

These include "strengthening surveillance, microbial detection and forensics and developing prototype vaccines and therapeutics against priority pathogens of pandemic potential" – new funding is not mentioned.

"It is a question of when, not if, another pandemic strikes,” leading British immunologist Sir John Bell wrote in April. "We must be in a constant state of readiness for the next big health crisis – if we do not act now, we will not be forgiven."

With a 38% chance of most people experiencing another pandemic in their lifetimes, UK's newly released biosecurity strategy could be a leading guide and is well put together. Whether policy makers can deliver on its ambitions, not least with another general election around the corner, is another question. There is no question that the risk is mounting, experts agree.

Earlier this year, Sophie Rose, biosecurity policy manager at the Centre for Long-Term Resilience said: "Advancements in our ability to synthesise DNA sequences unlock new ways to acquire,develop and produce biological weapons,whilst machine learning algorithms may eventually facilitate the identification of novel,more deadly pathogens and toxins."

She called for HMG to get its act together when it comes to biosecurity risks -- and quickly. As Rose emphasised: "The 2023 NBSS must be accompanied by,or rapidly followed up with, an implementation plan. Relevant HMG departments need to be provided with the resources required to deliver on the commitments in the strategy."

With increasing R&D in the field of life sciences, the likelihood of an accidental pathogen leak with devastating consequences has also increased.

"We can defeat the threats of the future - but only if we refuse to stand still, and instead continue to innovate and strengthen our health resilience to protect the future wellbeing and economic security of the UK," writes Deputy Prime Minister Oliver Dowden in his introduction to the country's biological security roadmap.

"We are home to some of the best universities in the world. We have the highest number of unicorns in Europe, and we are the continent's leading biotech hub in breakthrough life-sciences start-ups," goes on Dowden's vote of confidence in the strategy- but the technology that the strategy aspires to doesn't exist yet. And Britain needs far more consistent policy and funding plans to ensure that when this technology does come into play, its on domestic soil with an alliance to national interest.

The NBSS paper builds on a 2018 biological security strategy from the Home Office, Department of Health and Social Care, and Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs. The subsequent pandemic has no doubt focused attention on the risks – which are ample. Experts from University of Oxford's Future of Humanity (FIH) Institute have iterated the level of threat in their 'Future Proof' report, for example, with lead author Toby Ord said that the likelihood of the world experiencing an existential catastrophe over the next one hundred years, such as a human-caused pandemic "is one in six" and akin to playing "Russian roulette."

The FIH's report stated that the UK government has a tendency to "prepare to fight the last war" and focus only on the types of disasters that have occurred in the past. The government has promised £1.5 billion of investment each year towards the new "biothreats radar" but more work needs to be done on execution.

As Cassidy Nelson, head of biosecurity policy at the Centre for Long-Term Resilience, commented: “This much-needed strategy underscores the UK’s role as a global leader in enhancing resilience against biological risks We welcome the goal to achieve resilience to the full spectrum of biological threats by 2030 and commend the use of built-in accountability measures to drive the implementation of the strategy. We now need sustained resourcing and prioritisation to achieve tangible improvements to the UK’s biosecurity capabilities on such an ambitious timeline”.

Earlier this year meanwhile, the UK government cut earmarked funding for smaller life science companies. Kate Bingham, of SV Health investors had then said that the UK was squandering its opportunity to be a life sciences superpower as it was letting, "short-term pressures are crowd out long-term solutions."

The biosecurity strategy states that its mission is to "to implement a UK-wide

approach to biosecurity which strengthens, deterrence and resilience," and to succeed at this, Britain does need to be able to build-up and maintain its industries. There is a lot of work to do on executing the NBSS.

Strong views on this? Get in touch.